Manifestos for Design and More…

Today I found myself signing the First Things First 2020 Manifesto. As a designer, I’m taking a stand to take on climate action. Will you join me? Sign the manifesto, firstthingsfirst2020.org #firstthingsfirst2020

2020 Edition

We, the undersigned, are designers who have been raised in a world in which we put profit over people and the planet in an attempt to keep the gears of capitalism greased and well maintained. Our time and energy are increasingly used to manufacture demand, to exploit populations, to extract resources, to fill landfills, to pollute the air, to promote colonization, and to propel our planet’s sixth mass extinction. We have helped to create comfortable, happy lives for some of our species and allowed harm to others; our designs, at times, serve to exclude, eliminate, and discriminate.

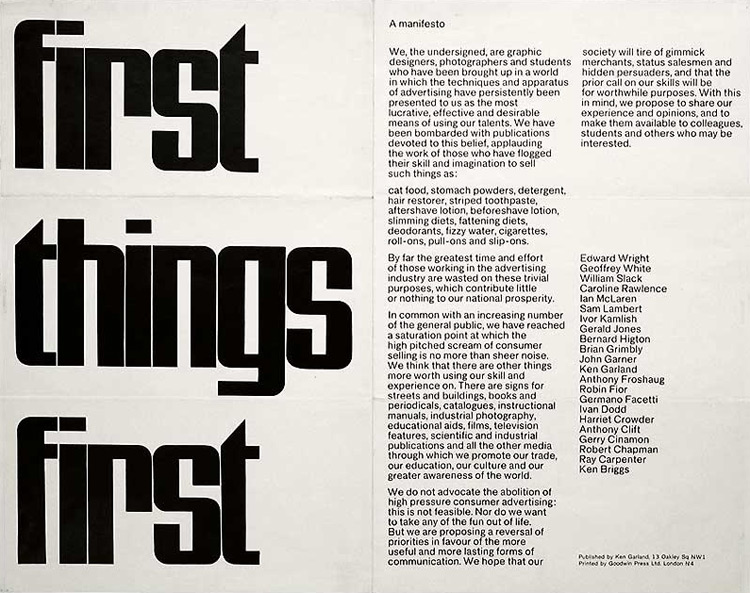

The Original First Things First

Published in 1964 by Ken Garland along with 20 other designers, photographers and students, the manifesto was a reaction to the staunch society of 1960s Britain and called for a return to a humanist aspect of design.

In 1964, 22 visual communicators signed the original call for our skills to be put to worthwhile use. With the explosive growth of global commercial culture, their message has only grown more urgent. Today, we renew their manifesto in expectation that no more decades will pass before it is taken to heart.

First Things First Manifesto 2000

This manifesto was first published in 1999 in Emigre 51.

We, the undersigned, are graphic designers, art directors and visual communicators who have been raised in a world in which the techniques and apparatus of advertising have persistently been presented to us as the most lucrative, effective and desirable use of our talents. Many design teachers and mentors promote this belief; the market rewards it; a tide of books and publications reinforces it

MANIFESTO WARS

by Steven Heller

“A true manifesto will make those who do not agree wince. That’s the point. Make a statement and then act upon” —Steven Heller

During the turbulent teens and cantankerous twenties artists’ manifestos were as common as weeds, and just as fast to sprout up from a groundswell of radical activity. Manifestos were statements of purpose, calls to action and weapons of mass obstruction.

Words were the lethal ammunition. Sometimes they were aimed with pinpoint intelligence, other times they sprayed the battlefield with rampant stupidity. Manifestos came in all degrees of simplicity or complexity. They were long or short depending on the writer’s proclivities. Some survived, others are long forgotten—and the better for it. All tried to make a mark.

Today manifestos are back. Artists who have decided it is their respective mission to save the world, or even those who have less ambitious goals, routinely turn first to a manifesto—a statement of principles—and then to their art forms to state how, why and where. As they were in the teens and twenties (and thirties and forties and fifties and sixties, etcetera), some manifestos are worth the paper they are written on, while others are not worthy of the trees they destroyed (perhaps a manifesto about manifestos is due).

Yet even the most worthy often have a hollow ring. No matter how smart the manifesto may be, words are empty without action to support them.

Therefore, the Ten Commandments—a manifesto by any other name—has some weight (not just as heavy stone tablets) because millions of people have more or less followed and sometimes violently acted out the “thou shalts and thou shalt nots” to the letter. Of course, this divine manifesto was actually created by men, and the Ten Commandments contain all the flaws that men had in those early biblical times. In other words, even a finely composed manifesto born of well–meaning sentiments is not always an exemplary one. Manifestos are by nature built on prejudice for or against something. They are also dictates to do something that someone else thinks important or necessary. Follow me because I am right is the implication of a manifesto—is it not?

But there is a genus of manifesto that is not just a commandment to follow or movement to join. The personal manifesto is not implicitly telling you or me what to do; it is tell you or me what the individual who wrote it believes. And if there is a chance that the ideas contained in the manifesto touch a chord in other individuals, then all the better. A personal manifesto is a declaration of principles, not an order to forge ahead, damn the torpedoes or change the world in a particular image.

The past ten years—let’s say since the turn of the twenty–first century, because the fin de siecle is always a moment when new things occur—had been a fertile period for personal manifestos, and particularly in art and design circles. Some of those who have issued such declarations call them “to–do–lists,” others are more high–falutin. Manifestos are everywhere in art and design books, spoken at conferences, shouted from the rooftops. The creators are telling anyone who listens: “This is what I am going to do, and perhaps you’d be happier doing it too!”

Sarcasm aside, a manifesto is a double–edged sword. It can articulate goals and desires in an honest and inspiring way. It can also be perceived as so much babble— pretense of the highest order—and must be ignored.

Does that mean a manifesto should be written in any “standard” manner to avoid critique and be pure of meaning? No! A true manifesto will make those who do not agree wince. That’s the point. Make a statement and then act upon them that does change something—whatever it may be. The most memorable manifestos have altered the way we think and do. A manifesto should be a declaration of war against complacency. Shit! That almost sounds like a manifesto.

Steven Heller, Design critic

MANUFACTURING QUALITY DISSENT SINCE 1989

When I first discovered the street art face that evolved into Obey Giant I did not understand its meaning, only its pervasiveness. I learned more about it through Shepard Fairey’s manifesto—check it out, it is a worthy case study.

The OBEY sticker campaign can be explained as an experiment in Phenomenology. Heidegger describes Phenomenology as “the process of letting things manifest themselves.” Phenomenology attempts to enable people to see clearly something that is right before their eyes but obscured; things that are so taken for granted that they are muted by abstract observation.

The first aim of phenomenology is to reawaken a sense of wonder about one’s environment. The obey sticker attempts to stimulate curiosity and bring people to question both the sticker and their relationship with their surroundings.

Here’s a great one from Tibor Kalman written in 1998

FUCK COMMITTEES

Tibor Kalman

(I believe in lunatics)

It’s about the struggle between individuals with jagged passion in their work and today’s faceless corporate committees, which claim to understand the needs of the mass audience, and are removing the idiosyncrasies, polishing the jags, creating a thought-free, passion-free, cultural mush that will not be hated nor loved by anyone. By now, virtually all media, architecture, product and graphic design have been freed from ideas, individual passion, and have been relegated to a role of corporate servitude, carrying out corporate strategies and increasing stock prices. Creative people are now working for the bottom line.

Magazine editors have lost their editorial independence, and work for committees of publishers (who work for committees of advertisers). TV scripts are vetted by producers, advertisers, lawyers, research specialists, layers and layers of paid executives who determine whether the scripts are dumb enough to amuse what they call the ‘lowest common denominator’. Film studios out films in front of focus groups to determine whether an ending will please target audiences. All cars look the same. Architectural decisions are made by accountants. Ads are stupid. Theater is dead.

Corporations have become the sole arbiters of cultural ideas and taste in America. Our culture is corporate culture.Culture used to be the opposite of commerce, not a fast track to ‘content’- derived riches. Not so long ago captains of industry (no angels in the way they acquired wealth) thought that part of their responsibility was to use their millions to support culture. Carnegie built libraries, Rockefeller built art museums, Ford created his global foundation. What do we now get from our billionaires? Gates? Or Eisner? Or Redstone? Sales pitches. Junk mail. Meanwhile, creative people have their work reduced to ‘content’ or ‘intellectual property’. Magazines and films become ‘delivery systems’ for product messages.

But to be fair, the above is only 99 percent true.

I offer a modest solution: Find the cracks in the wall. There are a very few lunatic entrepreneurs who will understand that culture and design are not about fatter wallets, but about creating a future. They will understand that wealth is means, not an end. Under other circumstances they may have turned out to be like you, creative lunatics. Believe me, they’re there and when you find them, treat them well and use their money to change the world.

Tibor Kalman

New York

June 1998

AN INCOMPLETE MANIFESTO FOR GROWTH

Bruce Mau

- Allow events to change you. You have to be willing to grow. Growth is different from something that happens to you. You produce it. You live it. The prerequisites for growth: the openness to experience events and the willingness to be changed by them.

- Forget about good. Good is a known quantity. Good is what we all agree on. Growth is not necessarily good. Growth is an exploration of unlit recesses that may or may not yield to our research. As long as you stick to good you’ll never have real growth.

- Process is more important than outcome. When the outcome drives the process we will only ever go to where we’ve already been. If process drives outcome we may not know where we’re going, but we will know we want to be there.

- Love your experiments (as you would an ugly child). Joy is the engine of growth. Exploit the liberty in casting your work as beautiful experiments, iterations, attempts, trials, and errors. Take the long view and allow yourself the fun of failure every day.

- Go deep. The deeper you go the more likely you will discover something of value.

- Capture accidents. The wrong answer is the right answer in search of a different question. Collect wrong answers as part of the process. Ask different questions.

- Study. A studio is a place of study. Use the necessity of production as an excuse to study. Everyone will benefit.

- Drift. Allow yourself to wander aimlessly. Explore adjacencies. Lack judgment. Postpone criticism.

- Begin anywhere. John Cage tells us that not knowing where to begin is a common form of paralysis. His advice: begin anywhere.

- Everyone is a leader. Growth happens. Whenever it does, allow it to emerge. Learn to follow when it makes sense. Let anyone lead.

- Harvest ideas. Edit applications. Ideas need a dynamic, fluid, generous environment to sustain life. Applications, on the other hand, benefit from critical rigor. Produce a high ratio of ideas to applications.

- Keep moving. The market and its operations have a tendency to reinforce success. Resist it. Allow failure and migration to be part of your practice.

- Slow down. Desynchronize from standard time frames and surprising opportunities may present themselves.

- Don’t be cool. Cool is conservative fear dressed in black. Free yourself from limits of this sort.

- Ask stupid questions. Growth is fuelled by desire and innocence. Assess the answer, not the question. Imagine learning throughout your life at the rate of an infant.

- Collaborate. The space between people working together is filled with conflict, friction, strife, exhilaration, delight, and vast creative potential.

- ____________________. Intentionally left blank. Allow space for the ideas you haven’t had yet, and for the ideas of others.

- Stay up late. Strange things happen when you’ve gone too far, been up too long, worked too hard, and you’re separated from the rest of the world.

- Work the metaphor. Every object has the capacity to stand for something other than what is apparent. Work on what it stands for.

- Be careful to take risks. Time is genetic. Today is the child of yesterday and the parent of tomorrow. The work you produce today will create your future.

- Repeat yourself. If you like it, do it again. If you don’t like it, do it again.

- Make your own tools. Hybridize your tools in order to build unique things. Even simple tools that are your own can yield entirely new avenues of exploration. Remember, tools amplify our capacities, so even a small tool can make a big difference.

- Stand on someone’s shoulders. You can travel farther carried on the accomplishments of those who came before you. And the view is so much better.

- Avoid software. The problem with software is that everyone has it.

- Don’t clean your desk. You might find something in the morning that you can’t see tonight.

- Don’t enter awards competitions. Just don’t. It’s not good for you.

- Read only left–hand pages. Marshall McLuhan did this. By decreasing the amount of information, we leave room for what he called our ‘noodle’.

- Make new words. Expand the lexicon. The new conditions demand a new way of thinking. The thinking demands new forms of expression. The expression generates new conditions.

- Think with your mind. Forget technology. Creativity is not device–dependent.

- Organization = Liberty. Real innovation in design, or any other field, happens in context. That context is usually some form of cooperatively managed enterprise. Frank Gehry, for instance, is only able to realize Bilbao because his studio can deliver it on budget. The myth of a split between ‘creatives’ and ‘suits’ is what Leonard Cohen calls a “charming artifact of the past.”

- Don’t borrow money. Once again, Frank Gehry’s advice. By maintaining financial control, we maintain creative control. It’s not exactly rocket science, but it’s surprising how hard it is to maintain this discipline, and how many have failed.

- Listen carefully. Every collaborator who enters our orbit brings with him or her a world more strange and complex than any we could ever hope to imagine. By listening to the details and the subtlety of their needs, desires, or ambitions, we fold their world onto our own. Neither party will ever be the same.

- Take field trips. The bandwidth of the world is greater than that of your TV set, or the Internet, or even a totally immersive, interactive, dynamically rendered, object–oriented, real–time, computer graphic–simulated environment.

- Make mistakes faster. This isn’t my idea—I borrowed it. I think it belongs to Andy Grove.

- Imitate. Don’t be shy about it. Try to get as close as you can. You’ll never get all the way, and the separation might be truly remarkable. We have only to look to Richard Hamilton and his version of Marcel Duchamp’s large glass to see how rich, discredited, and underused imitation is as a technique.

- Scat. When you forget the words, do what Ella did: make up something else… but not words.

- Break it, stretch it, bend it, crush it, crack it, fold it.

- Explore the other edge. Great liberty exists when we avoid trying to run with the technological pack. We can’t find the leading edge because it’s trampled underfoot. Try using old–tech equipment made obsolete by an economic cycle but still rich with potential.

- Coffee breaks, cab rides, green rooms. Real growth often happens outside of where we intend it to, in the interstitial spaces—what Dr. Seuss calls “the waiting place.” Hans Ulrich Obrist once organized a science and art conference with all of the infrastructure of a conference—the parties, chats, lunches, airport arrivals—but with no actual conference. Apparently it was hugely successful and spawned many ongoing collaborations.

- Avoid fields. Jump fences. Disciplinary boundaries and regulatory regimes are attempts to control the wilding of creative life. They are often understandable efforts to order what are manifold, complex, evolutionary processes. Our job is to jump the fences and cross the fields.

- Laugh. People visiting the studio often comment on how much we laugh. Since I’ve become aware of this, I use it as a barometer of how comfortably we are expressing ourselves.

- Remember. Growth is only possible as a product of history. Without memory, innovation is merely novelty. History gives growth a direction. But a memory is never perfect. Every memory is a degraded or composite image of a previous moment or event. That’s what makes us aware of its quality as a past and not a present. It means that every memory is new, a partial construct different from its source, and, as such, a potential for growth itself.

- Power to the people. Play can only happen when people feel they have control over their lives. We can’t be free agents if we’re not free.

08.19.13 Andrew Howard | Primary Sources

1. No amount of ingenuity or creativity can create strong, clear, memorable design solutions from confused thought. This is why design is first and foremost a means of organising ideas. Design is thinking made visible.

2. Opinion is welcomed but is not enough. Your ideas must be substantiated through facts and testing, through research and evaluation.

3. Solutions will always vary according to context, interpretation and objectives. There are no absolute answers. Learn instead to ask the right questions.

4. Regardless of any specific design interest or preference that you may have, in today’s world all designers need to develop a multi-form understanding that is able to respond to multiple communication needs and platforms. Thus multimedia is not a component of contemporary design, it is its definition.

5. Beware of fashion – it encourages the idea that nothing is lasting and that you always have to be on the move. If you are never still you will never encounter profundity. Learn to stay in the same place and dig deeper.

6. Take nothing for granted. Learn to question what you think you know. Remember that the extraordinary is as likely to reside in the ground beneath our feet as in the stars above our heads. Your ability will not simply be measured by your willingness to explore new ideas and new territory but also through the ways that you are able to apply new ideas to familiar territory.

7. Critical thought being central to design does not make technical and craft skills secondary. Visual communication is not simply dependent on the power of thought. It is a process of making – of transforming ideas into tangible expressions. Thinking and making are not alternatives to each other. They are forces of reciprocal power within the design process. One cannot take place without the other.

8. Every tool has its own characteristics, every visual technique its own expressiveness, and every form its own possibilities and limitations. Your success is dependent on your ability to manipulate that knowledge with skill and sensibility. You must learn your craft.

9. Design does not exist solely in the realm of the intellect. The power to enlighten, to celebrate, to inform and to disturb expectations also lies in the capacity to make emotional connections. Always use your head but never forget your heart.

10. You cannot succeed without commitment. You cannot thrive without passion. You cannot survive without pleasure. All these things, or their absence, will be reflected in your work. The resonance of design as a collective social project is in your hands.

THE PESTO MANIFESTO

Peter Nowogrodzki

This is the pesto manifesto; an improvised recipe of sorts. When making pesto, here are some things to keep in mind:

- Must use organic garlic if you live in the 21st Ce.

- Must use fresh basil from your mom or neighbor’s garden.

- Must use pine nuts.

- No food processing allowed.

These are important because pesto is a delicacy that deserves to be made right.

Pasta should not be smothered in mediocrity! Or should it?

- Become inspired by mediocre productions.

- Don’t covert production and experimentation recipe.

- Always leave the edges rough, so that someone can cut themselves.

- A photoshop’d joke is deep and meaningful.

- Take the knife to cultural icons and produce: produce the produce for the recipe and destroy the recipe.

- Follow and muddy up every else’s recipe; pun and play, annihilate and resurrect meaning.

Keep in mind: pesto is delicious when it’s made fresh.

Last Things Last

On 19, January, 2012 Ken Garland delivered Last Things Last – a contradictory follow up to his First Things First Manifesto from 1964.

On January 19, 2012, Ken Garland made a statement (Links to an external site.), contradicting his First Things First Manifesto from 1964.

“I believe it would be inappropriate for someone of my age – I am 82 – to make predictions about the trade, craft, or, if you must, profession of visual communication. Nor, if it comes to that, am I prepared to offer an update or revision of the First Things First manifesto of 1964 (see Eye 13). So what am I doing, heading for a symposium on manifestos [‘Manifesto Project’, Otrascosas de Villarrosàs gallery, Barcelona] as a speaker?

Well, first of all, I’m coming because I was invited: I guess I’m flattered to learn that some younger people in my business still think I have something to say to them.

Secondly, I love Barcelona and I am always glad to visit the city – especially if someone is prepared to pay for my airfare.

Thirdly, I want to hear what my younger colleagues have to say about their hopes for the future.

And fourthly, I do feel I must make a contribution of some sort to this occasion. But if not predictions or prescriptions, then what?

Maybe, if you will allow, I can take this opportunity to offer my deep gratitude to those who have offered me, these past 50 years, the most generous and enlightened support for my work on their behalf … my clients At the end of last year I had occasion to add them up and found they came to more than 50, wow!

What’s more, some of them were with me for twenty, fifteen, or a dozen years. Whatever would I have done without them?

Of course, you could say that not all clients are paragons; some, perhaps, are self-serving tricksters, devoted to wrenching profit from their innocent customers without a single qualm of conscience. Possibly: but I have never met one such.

As to my clients’ responses to the manifestos and other inflammatory impulses I’ve engaged in from time to time, I have a little story about this. After the flurry of publicity following the publication in January 1964 of First Things First, one of my clients took me out to lunch and when we got to the coffee stage he said: ‘Well, Ken, you’re putting yourself about a bit, laddie, appearing on television and proclaiming manifestos. All good fun, of course, but I wonder if you’re not being a bit, ah, irresponsible, if I may say so. Do hope this won’t frighten off some of your clients, know what I mean?’

To tell the truth, this possibility had never occurred to me, and in fact, my clients were totally unfazed by the manifesto; except, that is, for the one who had taken me to lunch, whom I never saw again.

That said, I have to confess that there was no acknowledgment in First Things First of the positive, creative part that could be played by the right kind of client. So now, some 48 years later, I’m making up for that omission.

This may come as a bit of a shock to those of you who believe we are engaged in some essential conflict between ‘us’ and ‘them’, with ‘us’ being the artists, designers, photographers, architects, and such-like who consider ourselves to be the truly creative part of the community, and ‘them’ being the business persons, entrepreneurs, and industrialists whom we are to regard as the ruthless exploiters of our skills.

Well, I don’t accept this simplistic picture. These unappetizing ‘them’ characters belong in fairy tales, along with Cinderella’s ugly sisters. Of course, some of them are not all they should be; but some of us aren’t all we should be either. So what?

So clients are – they must be – our partners. To those of you who hold yourselves aloof from things commercial, by virtue of academic posts, inherited wealth or vows of poverty, I say: ‘Good on you, dear people: do your thing, whatever that is.’ But as for myself and my sisters and brothers immersed in matters of commerce, we’ve been having a great time.

And I tell you this: when the socialist future I’ve always worked for finally arrives, there will still be goods and services to be promoted and, yes, sold. And we, or more likely our grandchildren, will be there in the middle of it, still having a great time, getting our hands dirty.

And this just may be my last word on the subject. Maybe.”

0 Comments